24.1. Packets¶

The design of the Packet framework of ns was heavily guided by a few important use-cases:

avoid changing the core of the simulator to introduce new types of packet headers or trailers

maximize the ease of integration with real-world code and systems

make it easy to support fragmentation, defragmentation, and, concatenation which are important, especially in wireless systems.

make memory management of this object efficient

allow actual application data or dummy application bytes for emulated applications

Each network packet contains a byte buffer, a set of byte tags, a set of packet tags, and metadata.

The byte buffer stores the serialized content of the headers and trailers added to a packet. The serialized representation of these headers is expected to match that of real network packets bit for bit (although nothing forces you to do this) which means that the content of a packet buffer is expected to be that of a real packet.

Fragmentation and defragmentation are quite natural to implement within this context: since we have a buffer of real bytes, we can split it in multiple fragments and re-assemble these fragments. We expect that this choice will make it really easy to wrap our Packet data structure within Linux-style skb or BSD-style mbuf to integrate real-world kernel code in the simulator. We also expect that performing a real-time plug of the simulator to a real-world network will be easy.

One problem that this design choice raises is that it is difficult to pretty-print the packet headers without context. The packet metadata describes the type of the headers and trailers which were serialized in the byte buffer. The maintenance of metadata is optional and disabled by default. To enable it, you must call Packet::EnablePrinting() and this will allow you to get non-empty output from Packet::Print and Packet::Print.

Also, developers often want to store data in packet objects that is not found in the real packets (such as timestamps or flow-ids). The Packet class deals with this requirement by storing a set of tags (class Tag). We have found two classes of use cases for these tags, which leads to two different types of tags. So-called ‘byte’ tags are used to tag a subset of the bytes in the packet byte buffer while ‘packet’ tags are used to tag the packet itself. The main difference between these two kinds of tags is what happens when packets are copied, fragmented, and reassembled: ‘byte’ tags follow bytes while ‘packet’ tags follow packets. Another important difference between these two kinds of tags is that byte tags cannot be removed and are expected to be written once, and read many times, while packet tags are expected to be written once, read many times, and removed exactly once. An example of a ‘byte’ tag is a FlowIdTag which contains a flow id and is set by the application generating traffic. An example of a ‘packet’ tag is a cross-layer QoS class id set by an application and processed by a lower-level MAC layer.

Memory management of Packet objects is entirely automatic and extremely efficient: memory for the application-level payload can be modeled by a virtual buffer of zero-filled bytes for which memory is never allocated unless explicitly requested by the user or unless the packet is fragmented or serialized out to a real network device. Furthermore, copying, adding, and, removing headers or trailers to a packet has been optimized to be virtually free through a technique known as Copy On Write.

Packets (messages) are fundamental objects in the simulator and their design is important from a performance and resource management perspective. There are various ways to design the simulation packet, and tradeoffs among the different approaches. In particular, there is a tension between ease-of-use, performance, and safe interface design.

24.1.1. Packet design overview¶

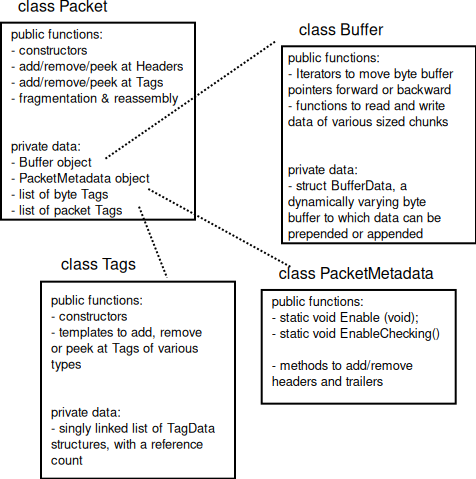

Unlike ns-2, in which Packet objects contain a buffer of C++ structures corresponding to protocol headers, each network packet in ns-3 contains a byte Buffer, a list of byte Tags, a list of packet Tags, and a PacketMetadata object:

The byte buffer stores the serialized content of the chunks added to a packet. The serialized representation of these chunks is expected to match that of real network packets bit for bit (although nothing forces you to do this) which means that the content of a packet buffer is expected to be that of a real packet. Packets can also be created with an arbitrary zero-filled payload for which no real memory is allocated.

Each list of tags stores an arbitrarily large set of arbitrary user-provided data structures in the packet. Each Tag is uniquely identified by its type; only one instance of each type of data structure is allowed in a list of tags. These tags typically contain per-packet cross-layer information or flow identifiers (i.e., things that you wouldn’t find in the bits on the wire).

Implementation overview of Packet class.¶

Figure Implementation overview of Packet class. is a high-level overview of the Packet implementation; more detail on the byte Buffer implementation is provided later in Figure Implementation overview of a packet’s byte Buffer.. In ns-3, the Packet byte buffer is analogous to a Linux skbuff or BSD mbuf; it is a serialized representation of the actual data in the packet. The tag lists are containers for extra items useful for simulation convenience; if a Packet is converted to an emulated packet and put over an actual network, the tags are stripped off and the byte buffer is copied directly into a real packet.

Packets are reference counted objects. They are handled with smart pointer (Ptr) objects like many of the objects in the ns-3 system. One small difference you will see is that class Packet does not inherit from class Object or class RefCountBase, and implements the Ref() and Unref() methods directly. This was designed to avoid the overhead of a vtable in class Packet.

The Packet class is designed to be copied cheaply; the overall design is based on Copy on Write (COW). When there are multiple references to a packet object, and there is an operation on one of them, only so-called “dirty” operations will trigger a deep copy of the packet:

ns3::Packet::AddHeader()ns3::Packet::AddTrailer()both versions of ns3::Packet::AddAtEnd()Packet::RemovePacketTag()

The fundamental classes for adding to and removing from the byte buffer are

class Header and class Trailer. Headers are more common but the below

discussion also largely applies to protocols using trailers. Every protocol

header that needs to be inserted and removed from a Packet instance should

derive from the abstract Header base class and implement the private pure

virtual methods listed below:

ns3::Header::SerializeTo()ns3::Header::DeserializeFrom()ns3::Header::GetSerializedSize()ns3::Header::PrintTo()

Basically, the first three functions are used to serialize and deserialize

protocol control information to/from a Buffer. For example, one may define

class TCPHeader : public Header. The TCPHeader object will typically

consist of some private data (like a sequence number) and public interface

access functions (such as checking the bounds of an input). But the underlying

representation of the TCPHeader in a Packet Buffer is 20 serialized bytes (plus

TCP options). The TCPHeader::SerializeTo() function would therefore be designed

to write these 20 bytes properly into the packet, in network byte order. The

last function is used to define how the Header object prints itself onto an

output stream.

Similarly, user-defined Tags can be appended to the packet. Unlike Headers, Tags are not serialized into a contiguous buffer but are stored in lists. Tags can be flexibly defined to be any type, but there can only be one instance of any particular object type in the Tags buffer at any time.

24.1.2. Using the packet interface¶

This section describes how to create and use the ns3::Packet object.

24.1.2.1. Creating a new packet¶

The following command will create a new packet with a new unique Id.:

Ptr<Packet> pkt = Create<Packet>();

What is the Uid (unique Id)? It is an internal id that the system uses to identify packets. It can be fetched via the following method:

uint32_t uid = pkt->GetUid();

But please note the following. This uid is an internal uid and cannot be counted on to provide an accurate counter of how many “simulated packets” of a particular protocol are in the system. It is not trivial to make this uid into such a counter, because of questions such as what should the uid be when the packet is sent over broadcast media, or when fragmentation occurs. If a user wants to trace actual packet counts, he or she should look at e.g. the IP ID field or transport sequence numbers, or other packet or frame counters at other protocol layers.

We mentioned above that it is possible to create packets with zero-filled payloads that do not actually require a memory allocation (i.e., the packet may behave, when delays such as serialization or transmission delays are computed, to have a certain number of payload bytes, but the bytes will only be allocated on-demand when needed). The command to do this is, when the packet is created:

Ptr<Packet> pkt = Create<Packet>(N);

where N is a positive integer.

The packet now has a size of N bytes, which can be verified by the GetSize() method:

/**

* \returns the size in bytes of the packet (including the zero-filled

* initial payload)

*/

uint32_t GetSize() const;

You can also initialize a packet with a character buffer. The input data is copied and the input buffer is untouched. The constructor applied is:

Packet(uint8_t const *buffer, uint32_t size);

Here is an example:

Ptr<Packet> pkt1 = Create<Packet>(reinterpret_cast<const uint8_t*>("hello"), 5);

Packets are freed when there are no more references to them, as with all ns-3 objects referenced by the Ptr class.

24.1.2.2. Adding and removing Buffer data¶

After the initial packet creation (which may possibly create some fake initial bytes of payload), all subsequent buffer data is added by adding objects of class Header or class Trailer. Note that, even if you are in the application layer, handling packets, and want to write application data, you write it as an ns3::Header or ns3::Trailer. If you add a Header, it is prepended to the packet, and if you add a Trailer, it is added to the end of the packet. If you have no data in the packet, then it makes no difference whether you add a Header or Trailer. Since the APIs and classes for header and trailer are pretty much identical, we’ll just look at class Header here.

The first step is to create a new header class. All new Header classes must inherit from class Header, and implement the following methods:

Serialize ()Deserialize ()GetSerializedSize ()Print ()

To see a simple example of how these are done, look at the UdpHeader class headers src/internet/model/udp-header.cc. There are many other examples within the source code.

Once you have a header (or you have a preexisting header), the following Packet API can be used to add or remove such headers.:

/**

* Add header to this packet. This method invokes the

* Header::GetSerializedSize and Header::Serialize

* methods to reserve space in the buffer and request the

* header to serialize itself in the packet buffer.

*

* \param header a reference to the header to add to this packet.

*/

void AddHeader(const Header & header);

/**

* Deserialize and remove the header from the internal buffer.

*

* This method invokes Header::Deserialize(begin) and should be used for

* fixed-length headers.

*

* \param header a reference to the header to remove from the internal buffer.

* \returns the number of bytes removed from the packet.

*/

uint32_t RemoveHeader(Header &header);

/**

* Deserialize but does _not_ remove the header from the internal buffer.

* This method invokes Header::Deserialize.

*

* \param header a reference to the header to read from the internal buffer.

* \returns the number of bytes read from the packet.

*/

uint32_t PeekHeader(Header &header) const;

For instance, here are the typical operations to add and remove a UDP header.:

// add header

Ptr<Packet> packet = Create<Packet>();

UdpHeader udpHeader;

// Fill out udpHeader fields appropriately

packet->AddHeader(udpHeader);

...

// remove header

UdpHeader udpHeader;

packet->RemoveHeader(udpHeader);

// Read udpHeader fields as needed

If the header is variable-length, then another variant of RemoveHeader() is needed:

/**

* \brief Deserialize and remove the header from the internal buffer.

*

* This method invokes Header::Deserialize(begin, end) and should be

* used for variable-length headers (where the size is determined somehow

* by the caller).

*

* \param header a reference to the header to remove from the internal buffer.

* \param size number of bytes to deserialize

* \returns the number of bytes removed from the packet.

*/

uint32_t RemoveHeader(Header &header, uint32_t size);

In this case, the caller must figure out and provide the right ‘size’ as an argument (the Deserialization routine may not know when to stop). An example of this type of header would be a series of Type-Length-Value (TLV) information elements, where the ending point of the series of TLVs can be deduced from the packet length.

24.1.2.4. Fragmentation and concatenation¶

Packets may be fragmented or merged together. For example, to fragment a packet

p of 90 bytes into two packets, one containing the first 10 bytes and the

other containing the remaining 80, one may call the following code:

Ptr<Packet> frag0 = p->CreateFragment(0, 10);

Ptr<Packet> frag1 = p->CreateFragment(10, 90);

As discussed above, the packet tags from p will follow to both packet

fragments, and the byte tags will follow the byte ranges as needed.

Now, to put them back together:

frag0->AddAtEnd(frag1);

Now frag0 should be equivalent to the original packet p. If, however, there

were operations on the fragments before being reassembled (such as tag

operations or header operations), the new packet will not be the same.

24.1.2.5. Enabling metadata¶

We mentioned above that packets, being on-the-wire representations of byte buffers, present a problem to print out in a structured way unless the printing function has access to the context of the header. For instance, consider a tcpdump-like printer that wants to pretty-print the contents of a packet.

To enable this usage, packets may have metadata enabled (disabled by default for

performance reasons). This class is used by the Packet class to record every

operation performed on the packet’s buffer, and provides an implementation of

Packet::Print () method that uses the metadata to analyze the content of the

packet’s buffer.

The metadata is also used to perform extensive sanity checks at runtime when performing operations on a Packet. For example, this metadata is used to verify that when you remove a header from a packet, this same header was actually present at the front of the packet. These errors will be detected and will abort the program.

To enable this operation, users will typically insert one or both of these statements at the beginning of their programs:

Packet::EnablePrinting();

Packet::EnableChecking();

24.1.3. Sample programs¶

See src/network/examples/main-packet-header.cc and src/network/examples/main-packet-tag.cc.

24.1.4. Implementation details¶

24.1.4.1. Private member variables¶

A Packet object’s interface provides access to some private data:

Buffer m_buffer;

ByteTagList m_byteTagList;

PacketTagList m_packetTagList;

PacketMetadata m_metadata;

mutable uint32_t m_refCount;

static uint32_t m_globalUid;

Each Packet has a Buffer and two Tags lists, a PacketMetadata object, and a ref count. A static member variable keeps track of the UIDs allocated. The actual uid of the packet is stored in the PacketMetadata.

Note: that real network packets do not have a UID; the UID is therefore an instance of data that normally would be stored as a Tag in the packet. However, it was felt that a UID is a special case that is so often used in simulations that it would be more convenient to store it in a member variable.

24.1.4.2. Buffer implementation¶

Class Buffer represents a buffer of bytes. Its size is automatically adjusted to hold any data prepended or appended by the user. Its implementation is optimized to ensure that the number of buffer resizes is minimized, by creating new Buffers of the maximum size ever used. The correct maximum size is learned at runtime during use by recording the maximum size of each packet.

Authors of new Header or Trailer classes need to know the public API of the Buffer class. (add summary here)

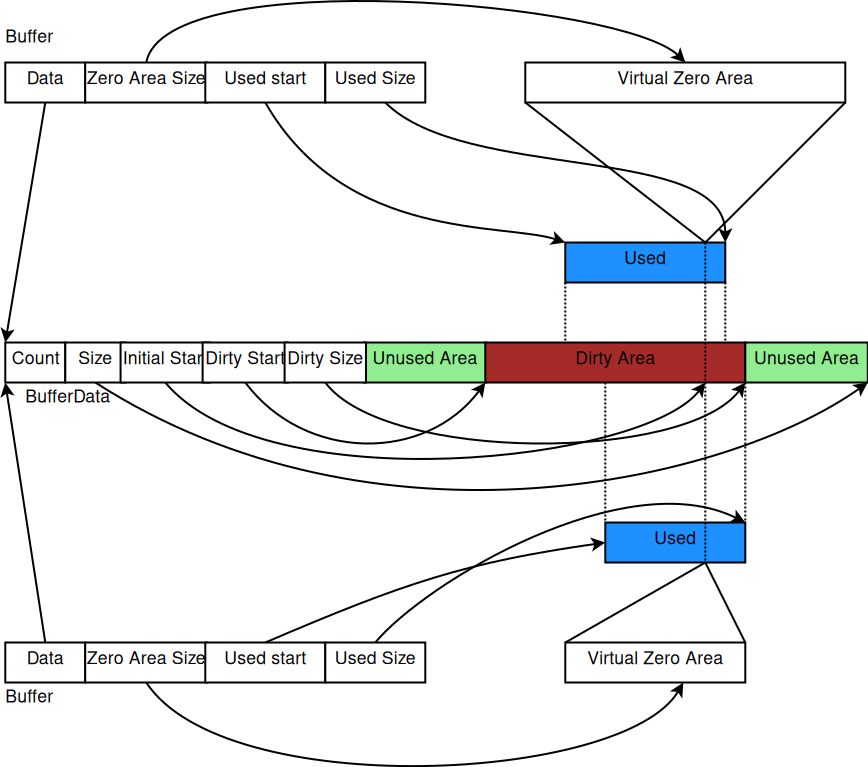

The byte buffer is implemented as follows:

struct BufferData {

uint32_t m_count;

uint32_t m_size;

uint32_t m_initialStart;

uint32_t m_dirtyStart;

uint32_t m_dirtySize;

uint8_t m_data[1];

};

struct BufferData *m_data;

uint32_t m_zeroAreaSize;

uint32_t m_start;

uint32_t m_size;

BufferData::m_count: reference count for BufferData structureBufferData::m_size: size of data buffer stored in BufferData structureBufferData::m_initialStart: offset from start of data buffer where data was first insertedBufferData::m_dirtyStart: offset from start of buffer where every Buffer which holds a reference to this BufferData instance have written data so farBufferData::m_dirtySize: size of area where data has been written so farBufferData::m_data: pointer to data bufferBuffer::m_zeroAreaSize: size of zero area which extends beforem_initialStartBuffer::m_start: offset from start of buffer to area used by this bufferBuffer::m_size: size of area used by this Buffer in its BufferData structure

Implementation overview of a packet’s byte Buffer.¶

This data structure is summarized in Figure Implementation overview of a packet’s byte Buffer.. Each Buffer holds a pointer to an instance of a BufferData. Most Buffers should be able to share the same underlying BufferData and thus simply increase the BufferData’s reference count. If they have to change the content of a BufferData inside the Dirty Area, and if the reference count is not one, they first create a copy of the BufferData and then complete their state-changing operation.

24.1.4.4. Memory management¶

Describe dataless vs. data-full packets.

24.1.4.5. Copy-on-write semantics¶

The current implementation of the byte buffers and tag list is based on COW (Copy On Write). An introduction to COW can be found in Scott Meyer’s “More Effective C++”, items 17 and 29). This design feature and aspects of the public interface borrows from the packet design of the Georgia Tech Network Simulator. This implementation of COW uses a customized reference counting smart pointer class.

What COW means is that copying packets without modifying them is very cheap (in terms of CPU and memory usage) and modifying them can be also very cheap. What is key for proper COW implementations is being able to detect when a given modification of the state of a packet triggers a full copy of the data prior to the modification: COW systems need to detect when an operation is “dirty” and must therefore invoke a true copy.

Dirty operations:

ns3::Packet::AddHeader

ns3::Packet::AddTrailer

both versions of ns3::Packet::AddAtEnd

ns3::Packet::RemovePacketTag

Non-dirty operations:

ns3::Packet::AddPacketTag

ns3::Packet::PeekPacketTag

ns3::Packet::RemoveAllPacketTags

ns3::Packet::AddByteTag

ns3::Packet::FindFirstMatchingByteTag

ns3::Packet::RemoveAllByteTags

ns3::Packet::RemoveHeader

ns3::Packet::RemoveTrailer

ns3::Packet::CreateFragment

ns3::Packet::RemoveAtStart

ns3::Packet::RemoveAtEnd

ns3::Packet::CopyData

Dirty operations will always be slower than non-dirty operations, sometimes by several orders of magnitude. However, even the dirty operations have been optimized for common use-cases which means that most of the time, these operations will not trigger data copies and will thus be still very fast.